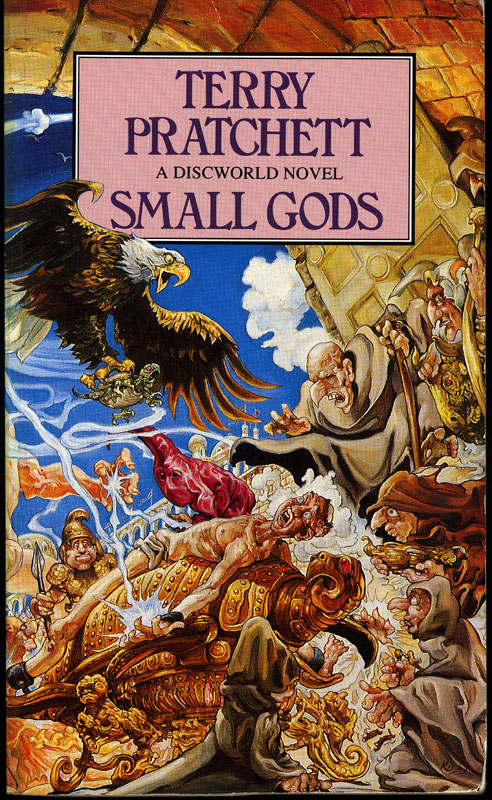

Small Gods

|

| Victor Gollancz |

Terry Pratchett

1992

Other Terry Pratchett Reviews- The Colour of Magic - The Light Fantastic - Equal Rites - Mort - Sourcery - Wyrd Sisters - Pyramids - Guards! Guards! - Eric - Moving Pictures - Reaper Man - Witches Abroad - Small Gods - Lords and Ladies - Men At Arms - Soul Music - Interesting Times - Maskerade - Feet of Clay - Hogfather - Raising Steam - A Blink of the Screen - Sky1 Adaptations- Dodger - The Long Earth (w Stephen Baxter)

"That's why it's always worth having a few philosophers around the place. One minute it's all Is Truth Beauty and Is Beauty Truth, and Does A Falling Tree in the Forest Make A Sound if There's No one There to Hear It, and then just when you think they're going to start dribbling one of 'em says, Incidentally, putting a thirty-foot parabolic reflector on a high place to shoot the rays of the sun at an enemy's ships would be a very interesting demonstration of optical principles."

When I made the decision to review the entire Discworld book series, I honestly didn't expect to get very far because I'm utterly awful at committing myself to writing projects. That has to be pretty evident through the fact that I very rarely update this blog more than once a week, or sometimes once a month. Life just seems to get in the way of writing somehow, even though these are hardly lengthy pieces. I actually started the Discworld reviews at least a year before I started this blog, when I was just idly rambling on forums (ironically gaining more hits than I do now), and at one point I gave up on that for ages, before something clicked in my brain and I got back to it. Now, twelve crummy reviews later, I've reached my absolute favourite book in the series. I adore Small Gods, not just as my preferred Discworld installment, but as an individual piece of literary brilliance.

By 1992, Terry Pratchett had struck creative gold with the Discworld, thanks to a series of brilliantly envisaged novels which were not only individually very good but also established a group of very successful series-within-series that involved re-occurring characters on an unofficial rotation schedule; Rincewind, the first creation, then Death, the Witches, and the Watch, each offering a different perspective on the same shared universe, as it grew exponentially larger and larger. So far, twelve books in, Pratchett had only written Pyramids and Moving Pictures as stand alone novels, and both of those had predominantly featured the city of Ankh-Morpork and other recognisable features from previous installments. Each book had also been in a vague chronological order, with Rincewind's early adventures and Mort set perhaps a few decades earlier than those proceeding. Pratchett seemingly loved developing his creations, pushing them forward as individuals and ideas, something which is emphasised more than ever in his recent books.

Small Gods, then, is sort of an anachronism in the Discworld series, and still stands alone today as such, yet I'm convinced it's the greatest Discworld novel by far; and that's not to be disparaging to any of the others, I just love it that much. To begin with it doesn't fit chronologically with the rest of the series, instead it seems to be set many years prior, probably hundreds of years. It wasn't really until the publication of the witches book Carpe Jugulum in 1998 that this was confirmed; the characters of Small Gods are confined to Discworld history, and (if you listen to Granny Weatherwax) disputed history at that. Secondly, the book doesn't go to Ankh-Morpork, and is instead set far across the Disc in a series of previously unexplored countries that should seem somewhat recognisable to the real world. These two features, combined with Pratchett's typical motif of the unsuspecting hero rising to indescribable success distinguishes this book from the pack and allows its epic adventure and heavy satire room to fully breathe.

.jpg)

The narrative is set at an undetermined time in the past in the previously unexplored country of Omnia, and is in part a traditional Pratchett-style coming-of-age story thickly layered in evocative satire and cultural analysis. It is by far the most detailed and intensive look that Pratchett takes at religion in any form, and it's heavily based upon certain aspects of European culture and history. It's story is based around one of Pratchett's more featured philosophical idea made real upon the Disc; that of belief. Omnia is a country based around its religion of Omnianism, where everyday life for Omnians involves being very careful to make sure they worship the church of the Great God Om in the correct and proper fashion. Making sure of this fact is the Quisition; that familiar-sounding faction of the church who's job it is to seek out unbelievers and heretics, and deal with them appropriately.

By 1992, Terry Pratchett had struck creative gold with the Discworld, thanks to a series of brilliantly envisaged novels which were not only individually very good but also established a group of very successful series-within-series that involved re-occurring characters on an unofficial rotation schedule; Rincewind, the first creation, then Death, the Witches, and the Watch, each offering a different perspective on the same shared universe, as it grew exponentially larger and larger. So far, twelve books in, Pratchett had only written Pyramids and Moving Pictures as stand alone novels, and both of those had predominantly featured the city of Ankh-Morpork and other recognisable features from previous installments. Each book had also been in a vague chronological order, with Rincewind's early adventures and Mort set perhaps a few decades earlier than those proceeding. Pratchett seemingly loved developing his creations, pushing them forward as individuals and ideas, something which is emphasised more than ever in his recent books.

Small Gods, then, is sort of an anachronism in the Discworld series, and still stands alone today as such, yet I'm convinced it's the greatest Discworld novel by far; and that's not to be disparaging to any of the others, I just love it that much. To begin with it doesn't fit chronologically with the rest of the series, instead it seems to be set many years prior, probably hundreds of years. It wasn't really until the publication of the witches book Carpe Jugulum in 1998 that this was confirmed; the characters of Small Gods are confined to Discworld history, and (if you listen to Granny Weatherwax) disputed history at that. Secondly, the book doesn't go to Ankh-Morpork, and is instead set far across the Disc in a series of previously unexplored countries that should seem somewhat recognisable to the real world. These two features, combined with Pratchett's typical motif of the unsuspecting hero rising to indescribable success distinguishes this book from the pack and allows its epic adventure and heavy satire room to fully breathe.

.jpg)

The narrative is set at an undetermined time in the past in the previously unexplored country of Omnia, and is in part a traditional Pratchett-style coming-of-age story thickly layered in evocative satire and cultural analysis. It is by far the most detailed and intensive look that Pratchett takes at religion in any form, and it's heavily based upon certain aspects of European culture and history. It's story is based around one of Pratchett's more featured philosophical idea made real upon the Disc; that of belief. Omnia is a country based around its religion of Omnianism, where everyday life for Omnians involves being very careful to make sure they worship the church of the Great God Om in the correct and proper fashion. Making sure of this fact is the Quisition; that familiar-sounding faction of the church who's job it is to seek out unbelievers and heretics, and deal with them appropriately.

The trouble is that the church is so powerful and dangerous that people don't really believe in Om anymore. It's the church which has become the focus of worship and fear and belief, and on the Discworld it's belief that really matters. The Great God Om has fallen from greatness, into the gutter. One morning he tried to manifest himself in the form of a great bull, but could only manage a tortoise and got stuck like that. Fortunately for the narrative, Om is lucky enough to encounter the one person who still actually really believes in him. Unfortunately that person is Brutha the Novice, who is considered by the kindliest of people to be a moron. But Brutha is the only person who can still here Om's voice, and so Om enlists him on the quest of restoring the god to greatness, resulting in adventures across the Disc, plenty of running away, and the wrath of the Quisition. Nobody expects the Omnian Quisition.

The key to the quality of Small Gods to me is not that it does anything majorly different from the typical Pratchett in terms of style or basic composition, but that it hits all of the regular notes perfectly. Firstly, and probably most importantly, it works as a comedic character piece just as well as a big, plot-driven adventure. Brutha and Om are a brilliant odd couple, surviving in spite of themselves and the massive odds against them. Brutha begins the book as a blank slate, knowing nothing but blind belief in Om, and develops on every page in the most dangerous and ridiculous circumstances. Om, the once great god, is almost the reverse of that as the formerly all-powerful deity struggles with his impotent form and almost total reliance of Brutha. Their opposition, the church itself, is represented by the cheerfully ruthless Vorbis, head of the Quisition. In the background lies a small underground resistance to the power of the church, a group who knows the real truth that the church tries to hide. The world is flat, not round, and lies on the back of a giant space turtle.

I suppose that the larger themes of Small Gods are rather simple to understand in nature, following on from opinions and poetical thought from romanticists like William Blake and virtually every other amateur philosopher who's thought about the pitfalls of well organised religion. Pratchett doesn't say anything new, but his portrayal is masterfully created. A portion of the book involves Brutha and Om temporarily escaping the borders of Omnia for the country of Ephebe, a thinly-veiled pastiche on popular portrayal of Ancient Greece, where toga-wearing philosophers stand on every street corner, desperately avoiding any job involving heavy lifting. Here Pratchett puts his spin on philosophy and classical philosopher's, creating a kind of Python-esque re-occurring sketch feel.

I suppose that the larger themes of Small Gods are rather simple to understand in nature, following on from opinions and poetical thought from romanticists like William Blake and virtually every other amateur philosopher who's thought about the pitfalls of well organised religion. Pratchett doesn't say anything new, but his portrayal is masterfully created. A portion of the book involves Brutha and Om temporarily escaping the borders of Omnia for the country of Ephebe, a thinly-veiled pastiche on popular portrayal of Ancient Greece, where toga-wearing philosophers stand on every street corner, desperately avoiding any job involving heavy lifting. Here Pratchett puts his spin on philosophy and classical philosopher's, creating a kind of Python-esque re-occurring sketch feel.The thing about Small Gods and the world of Omnia (which also reminds me of the Judea of Python's Life of Brian) is that it's so rich that I'd be thrilled to read a sequel or whole series continuing the story. At the very least, a sequel set in the present day on the Disc could be fabulous, but it seems that Pratchett has long been disinterested in the fringes of his universe, or anything not involving Ankh-Morpork. But then this probably exists better as a done-in-one story. Perhaps inevitably, the story leads to its natural resolution as Brutha takes his rightful place as prophet and leader, fulfilling his destiny despite bumbling his way through most of it. Om, frustrated and repressed for most of the book gets his moment of heroism and power, and everyone lives happily ever after, sort of.

For me, Pratchett never quite reached the heights of overall greatness that I experienced in Small Gods, as the combination of comedy, action, drama and philosophy all melds together in to one great novel. Pratchett continued to focus on his ongoing characters, leaving Brutha in the past as one who'd completed his journey. While there's always a chance he could choose to return to the characters (I never expected him to ever return to Esk of Equal Rites, for example), I doubt it'll happen, and Small Gods will continue to exist as an exemplary stand alone tale from the universe full of furious imagination and wonderfully crafty comedy. It'll surely always be my favourite, but there's plenty of greatness to come. Twenty-seven pieces of them, by my count.

No comments:

Post a Comment